SEZ Revival Tour? Kim Jong-un in Dandong

Every country exhibits certain disparities of power and prestige between capital and outlying regions. Yet, we frequently treat a nation’s capital as isomorphic with the state itself, underestimating the importance of peripheries. Kim Jong-un’s recent fourth trip to China is a case in point. The vast majority of stories filed about the visit were about action in Beijing, and none — particularly those stories sponsored by the Chinese Communist Party — looked at what happened in Dandong.

Places like Liaoning are where Beijing’s policy-making manifests, shaping provincial- and municipal-level interactions with North Korea. Here, Sino-NK founder Adam Cathcart zooms out from the halls of power in Beijing to analyze the implications of the fourth Xi-Kim summit for trade between China and the DPRK along the Yalu. Cross-referencing local government reports and footage from the Dandong train station, Cathcart presents insights into how officials at all levels seek to mitigate difficulties in cross-border trade between the PRC and North Korea. – Anthony Rinna, Senior Editor.

SEZ Revival Tour? Kim Jong-un in Dandong

by Adam Cathcart

Of the many essays looking at Kim Jong-un’s journey into China to kick off the year’s diplomatic action in Northeast Asia, few have had much to say about how China’s border regions are primed to engage with North Korea economically in the year ahead. The question of sanctions relief is of course important, as is the question of how directly and rigorously China will enforce the sanctions currently on the books. But what is missing throughout is what the recent visit will mean for the border areas, specifically Dandong. This essay finds that Kim Jong-un’s stopover and meeting with Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials in Dandong was not extensive, nor did it result in a breakthrough in some bureaucratic logjams on that part of the border. At the same time, China is maintaining readiness for more economic activity with North Korea in the zone, and Kim’s trip was preceded by some long-awaited connectivity between Dandong and Sinuiju city officials.

Frustrating the Americans | Sometimes North Korea has the ability to surprise with its relative transparency, and this was one of those occasions. With a few promising exceptions let loose on the first day of the visit, Chinese state media kept a fairly short leash on its commentary and reporting on the Kim Jong-un visit.

The Sejong Institute’s Lee Seong-hyon speculated that the drop-off in public news about the second day of Kim’s visit might have been calculated ‘psychological warfare’ meant to drive American analysts to frustration. While it makes for a juicy, speculative headline that accords with anxieties over US-China relations, Lee’s analysis was still not quite as juicy or speculative as that of his Sejong counterpart Cheong Seong-chang, who told the South China Morning Post in a paraphrased comment, “It cannot be ruled out that Kim and Xi will discuss shipping the North’s intercontinental ballistic missile out of the country to dismantle them, an issue that the US wanted to address.”

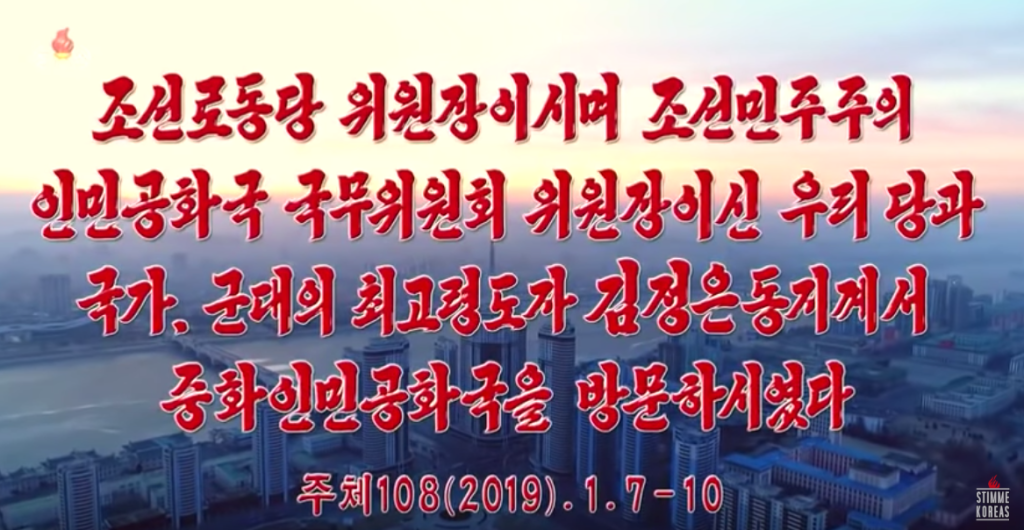

Perhaps. But leaving speculation aside and revealing far more than the CCP media did, the North Koreans themselves released 45 minutes of video footage on the evening of January 10. Starved for specificity and finding the official Beijing readout of the visits (whether in English or Chinese) to be less than satisfying, some observers surely saw the broadcast as a late Christmas gift for those who just wanted to know such things as if Kim had stopped in Dandong during his journey (he did), if Kim Ki-nam was back on the scene (he was not) and if Hwang Pyong-so would be near the end of Kim’s reception queue and grovelling (he was both).

Image: stimmekoreas YouTube channel

The big takeaway from the footage, without a doubt, was the Dandong stop-over on the way up and back. But all we really got from that city in terms of Western media reports was that some people had been asked to leave their hotel rooms so as not to spy Kim’s train.

More important is what Kim actually did in Dandong. With whom did he actually meet, and what might have they discussed?

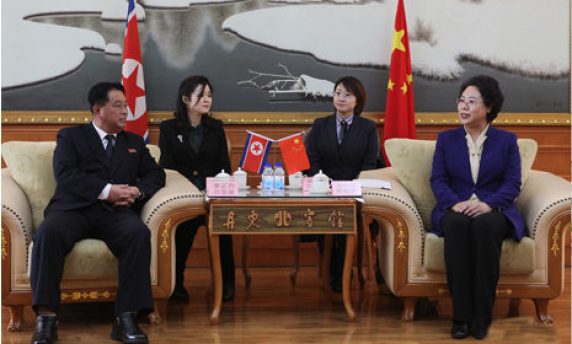

In Dandong, Kim met with a CCP delegation headed by International Liasion Department head Song Tao. That’s no surprise: Song Tao is one of Kim’s longer-known interlocutors. But Kim also greeted Ge Haiying, the Party Secretary for Dandong municipality, and an important person if designated special economic zones at Hwanggumpyeong and Wihwa Islands are ever going to get off the ground again.

Present there was Chen Qiufa, the CCP Party Secretary for Liaoning, as well as Lu Dongfu, the somewhat floppy-haired head of China’s railways corporation. Kim had met a variation on this delegation back in March 2018 during a previous trip through Dandong, and it seems from the footage that the meetings took place on Kim’s train, primarily making it a meet-and-greet rather than a time to hash out details on broader coordination across the border.

A Kim Incoming | On January 11, the North Korean party paper Rodong Sinmun provided a very convenient readout of the inbound meeting in Dandong:

The train carrying the Supreme Leader arrived in Dandong, border city of China, at 9.30 p.m. Beijing time on Jan. 7.

Seen at Dandong Railway Station to greet Kim Jong Un were Song Tao, head of the International Liaison Department of the C.C., CPC, Chen Qiufa, secretary of the Liaoning Provincial Party Committee, Lu Dongfu, general manager of the China Railway Corporation, Li Jinjun, Chinese ambassador to the DPRK, and Ge Haiying, secretary of the Dandong City Party Committee.

Kim Jong Un got off the train together with his wife Ri Sol Ju and exchanged warm greetings with the leading officials of the Chinese side. Song Tao offered the greeting of the heartfelt and warm welcome to Kim Jong Un upon authorization of General Secretary Xi Jinping and the Central Committee of the CPC. Kim Jong Un and Ri Sol Ju were presented with bunches of flowers by women.

Kim Jong Un had an amicable talk with Song Tao on the train. He expressed thanks to Song Tao for coming all the way to the border town, warmly welcoming him and according hospitality with sincerity, while guiding him to Beijing every time.

Saying that attaching great importance and significance to Kim Jong Un’s current visit to China at the special and vital time, Xi Jinping and the party and government of China made exceptional instructions to render good reception, Song Tao added that he would do his best for the satisfactory success of the meeting between the top leaders of the two parties and the two countries.

Kim then took an overnight train to Beijing, arriving at 10:55 a.m. Funnily, PRC ambassador Li Jinjun had clearly taken a fast train from Dandong and was again at the Beijing station to meet Kim Jong-un along with Song Tao and Lu Dongfu — a somewhat quirky reminder to the North Korean leader that he is travelling at the speed of the prior century, if in his own comfort, while Chinese officials and citizens are moving much, much faster.

None of this — namely, the stopover in Dandong or the short meeting there — was covered in mainland Chinese print media. This might have been for security reasons, but it might also have been to keep public expectations for development of the Sinuiju-Dandong corridor appropriately low.

As with the March 2018 visit, Ge Haiying was on the Supreme Leader’s train primarily to shake hands with Kim Jong-un. No formal meetings appear to have been held with the North Korean delegation. But did Ge Haiying and his new mayoral counterpart, Zhang Shuping, perhaps have meetings with North Koreans the next day, so as to pair up with the Xi-Kim meeting and demonstrate that the provinces were moving quickly to implement a closer economic relationship with North Korea? Of course they didn’t.

Ge Haiying instead chaired a meeting on 8 January which focused on “implementing the spirit of Xi Jinping’s inspection of the province” in late September 2018, and in which trade with North Korea, judging by the summary of the speech, would have very little to do with the “economic revitalization” of Liaoning or Dandong.

On January 9, Secretary Ge went up to Kuandian, a rural county also bordering North Korea, and gave a speech mainly dealing with poverty alleviation. Again, no references at all to the North Korean side, and no possible SEZ inference. Liaoning Party Secretary (essentially the governor, top job in the province) Chen Qiufa was at a follow-up meeting in Fengcheng, stating that “economic work in the year ahead will be difficult.” Chen’s remarks then ranged into a whole range of economic tasks for which North Korea would certainly be helpful (i.e., “enlarging the economy”) but none of which expressly dealt with foreign trade, cross-border trade, or the Belt and Road framework.

On the same day, Dandong’s new mayor Zhang Shuping went to a gathering of a subgroup of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference which included representatives from the worlds of industry and commerce. There she did what sounds like a fair amount of listening, and pledged to “use of all my energy to open up and solve the blockage points, painful points, and difficult points which hinder development (全力打通和解决制约发展的堵点、痛点、难点)” of Dandong. Which is about as close as she got to mentioning the DPRK, whose Supreme Leader she had apparently not been invited to meet. However, if Kim had in fact mentioned future projects dealing with Dandong, this would have been a venue in which Zhang could convey that informally.

But in sum, through the first two days of the Kim visit, there was nothing released or even implied from the Dandong or Liaoning governments that would give any notion that the Kim meetings in Dandong had resulted in anything resembling a breakthrough, let along a continuation of ongoing projects, in any of the following areas: SEZ cooperation, tourism, cross-border movement, cross-border infrastructure.

Liaoning officials largely went about their normal business in the days after meeting with Kim Jong-un.

For the time being, cross-border or cross-provincial cooperation with North Korea along the Yalu and Tumen rivers seems destined to be small in scale and entirely reversible. Take for instance the ceremony held in the early morning hours of New Years’ Day in Hunchun city’s Fangchuan district, where a new day tour to the small North Korean town of Dumangang was inaugurated.

Of course it is worth noting that this project is primarily about getting Chinese in to North Korea, not North Koreans into China. Russian travellers are large in number for Hunchun, and the city is working on increasing its capacity to process foreign travellers. However, coming back to Dandong, there was nothing akin to this Dagongbao piece published after Kim Jong-un made his big play for Sinuiju urban renewal in November 2018, explicitly calling attention to the connectivity between the two cities and economies, potentially.

In terms of ignoring the reality of Dandong (unconsummated economic ties with Sinuiju) for more amorphous puffery about Kim Jong-un’s focus on economic growth at home and, by implication, the need for Chinese support in that endeavor, Xinhua’s longest analysis of the visit really said it all. The piece was of course headlined with and illustrated by Kim Jong-un’s visit to a Chinese medicine factory in Beijing. Further still, the story was positively loaded with such exciting tidbits as how many times Kim Jong-un said the word “economic” or “economy” in his speech (“an 81% increase from his previous New Years’ Speech”), noting that his on-site inspections were becoming increasingly oriented toward economic development.

The same authoritative CCP version of the visit made explicit what was already obvious, doing so by invoking a familiar voicing: “South Korean media reported that Kim Jong-un’s train stopped at the Dandong train station.” In other words, no Chinese reporting could be done on this aspect of the visit.

This is not to say that Kim’s visit back in Dandong was entirely fruitless, or that Dandong’s top CCP officials simply went back to business as usual after his journey. As Kim Jong-un was slowly making his way back to Pyongyang, where he finally arrived at 3 p.m. on January 10, the new mayor of Dandong, Zhang Shuping, had what would be the last word. She held forth at a meeting of the Dandong Frontier Economic Cooperation Zone (somewhat confusingly, now called 边合区, short for Dandong bianjiang jingji hezuoqu), around Xinchengqu. In other words, she was talking to people whose responsibilities include the area around the new and still-unused Yalu River Bridge, overlooking the disused North Korean island of Hwanggumpyeong that was to have served as a centerpiece of joint economic development with the DPRK.

Her remarks included the following:

The Frontier Cooperation Economic Zone is an important driver for Dandong’s development and revitalization. We must have a long-range stance, establish and develop confidence, gather momentum for development, abandon the psychology of “being content to extend sovereignty over only part of the country” (偏安一隅, a saying from the Qing dynasty in reference to Southern Song general Yue Fei that in this case probably means that cadre should keep the greater good in mind and not be timid in telling individual bureaucrats that they cannot maintaining their own small kingdoms of influence), enhance the consciousness of development and opening up, focus on core business, and build the border area as a pilot area. [We should also] establish a new form of relationship between government and business [新型政商关系].

The text that emerged from Zhang Shuping’s meeting with Dandong’s administrators dealing with border-region economic cooperation was hardly as explicit in its aims as we saw in Liaoning party press last fall in a provincial look at how to implement the “One Belt, One Road” framework. In contrast, Zhang’s reported remarks did not so much as mention the Hwanggumpyeong or Wihwa Island SEZs and their joint management with North Korea. This was not the stuff of a breakthrough, but of maintaining readiness. At the very least, it would send a signal to Kim Jong-un and North Korean counterparts that China is serious about the matter and remains ready to cooperate on cross-border trade and to move forward with the SEZ projects previously agreed upon.

Although the border SEZs in the Yalu Estuary were the subject of several meetings of a joint management committee from approximately 2010-2012, they have been moribund since Jang Song-taek’s purge and execution in 2013, and no amount of gesticulating, performative urban planning and travelling by Kim Jong-un has brought back a functional North Korean interest in the projects. Instead, in early 2019, China has thus far had to content itself with a few dozen tourists trekking into a new frontier for North Korean tourism on the other end of the frozen border, and with hailing Kim Jong-un’s first visit of 2019 as a triumph for China’s centrality in global politics.

There was, however, one final sign that things are in fact on a slow track at the local level, and that the long-needed cross-provincial contacts are finally going forward, although they apparently had very little to do with Kim’s trip.

A Sinuiju government delegation went to Dandong on 27 and 28 December to wish a happy new year, and it included some of the same officials who had been present at Kim Jong-un’s November 16 briefing on the new city plan. Both Ge Haiying and Zhang Shuping met with the head of that delegation, Ri Chong-ryol, the chair of Sinuiju Government People’s Committee.

While no mention was made whatever of economic cooperation, much less the joint committees for Hwanggumpyeong, the North Koreans surely got the message that Xi Jinping is driving the Liaoning government and cadre in Dandong to find ways to get the economy moving faster.

While the glow of international klieg lights may have been bright indeed in Beijing, in Dandong the reality of interacting with North Korea to implement remains difficult to predict. Will the detente on the peninsula lead North Korea to be more confident in its cooperative dealings with China as regards frontier development? As the Dandong city government reminds us in a profile of Zhang Shuping, 70% of all North Korean exports go through Dandong.

A final shot from the documentary of Kim Jong-un’s China journey lingers: The cameraman leaned out of the train window, panning upwards at the Chinese inscription above the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge. Behind it, Sinuiju looked as dark as ever, but there may be more blueprinting going on in that murk than we are able to see.

No Comments